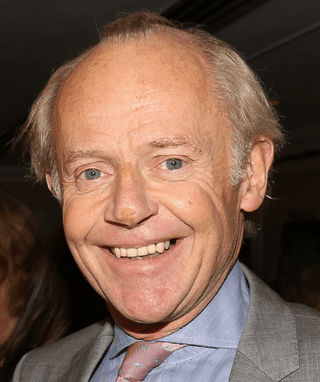

BAPAM is very lucky to be adding to its list of trustees, a real stalwart in the world of public relations.

Jonathan Morrish started in the music industry as a freelance music writer in the seventies, contributing to a number of different publications. Then in 1975 he joined Sony Music Entertainment, formerly known as CBS Records, as a house writer. Three years later he went on to manage their Press Office and worked closely with many of the company’s artists including amongst many, ABBA, the Beach Boys, Michael Jackson, Jamiroquai, Billy Joel, Meatloaf, Sade, Shakin’ Stevens, Wham! (with whom he went to China in 1985) and George Michael (including the famous court case in 1994. In 1995 he was appointed VP Comms and Corporate at PR Sony Music Europe.

In more recent times he held the post of Director of PR and Corporate Communications at music licensing charity, PPL for 8 years. He currently consults for them and a number of other companies on PR issues.

Besides the above he is also a trustee of The BRIT School in Croydon, and trustee of the BRIT Trust, the major charity of the British record industry. So on his recent visit to BAPAM, we jumped at the opportunity to talk to him about his illustrious career and his visions for our charity.

How do you feel about becoming a trustee at BAPAM? Why did you want to come on board?

I’ve been in the music business all my life. I’m completely not a musician but have always loved music and it’s always done a lot to me. I think music probably comes before language and if there is a universal language then it has to be music. It potentially binds people together and that is very powerful. I started life writing about music, one thing led to another and I joined a major record company in the 70s and in that time I worked with lots of different artists. I have seen some of the issues they had to go through, which in a funny way is as tough at the top of the tree as it is at the bottom. I have worked with people right at the top of the tree.

I think it’s very difficult to be a working musician in today’s world. Most people fail even if they have been signed to a record company as there’s only ten places in the top 10. So this is a tough place. I don’t think musicians are recognised, in fact it’s the same with all the creatives, because without them there is no industry. You can be as damaged by issues around you when you’re famous as you can be when you’re struggling to make your way. So for me working with BAPAM is really a chance to put something back. I’m also a trustee at the BRIT Trust which I love and am motivated for the same reasons, which is to be able to get kids in to the creative industries. So when CEO of PPL Peter Leatham and chairman of BAPAM approached me to join the charity it was a natural decision. The issues surrounding musicians is massive and this is a chance to harness a lot of what I think this organisation is capable of achieving.

It’s fair to say you have devoted your life to music and musicians, can you explain your passion for this industry?

I started as a press officer in the mid-seventies and really enjoyed being around musicians. I admire people who take it up as a profession. I like musicians, to me music is a kind of form of magic and I think the way it interacts with the brain is fascinating and that intrigues me. Music is a hot medium, it engages you. I look at the BRIT school and I see the way it brings people together and teaches you to be a team player.

…..During my time away at boarding school music was my outlet. This was in a world long before mobile phones and all of that. I would listen to the radio at prep school after lights out knowing that if I got caught I would get beaten. So music has always played a huge part in my life. It was a really different time back then. It’s hard for this generation to appreciate just how different it was. There were very few radio stations and now there are over 300. I can put on Spotify and just think about what I want to listen to. So that’s where we have to be careful and not cheapen music. What we have done in the process of having music on tap like water, is not to appreciate enough the people that make it and what they go through to make it. If you bought an album in 1964 the equivalent today would be over forty pounds, so music was expensive. I’m not necessarily saying that was right – it’s just the way the market was – but as the price of music has fallen so has the perceived value of musicians and that’s why what BAPAM is doing is so important. It’s recognising their health matters, health is everything. A healthy musician is going to perform better than an unhealthy musician.

Are there any particular projects you are excited about?

I think potentially looking at doing some awards, because what I think is really important is to raise the profile of BAPAM and then position it within the wider music business in a more recognised way than it is at the moment. These are areas where I think I can help.